When I visited London some time back, I also had the good fortune to see the Picasso (1881 – 1973) exhibition curated by Sir John Richardson “Minotaurs and Matadors” at the Gagosian Gallery. It’s woth noting that Richardson holds some knowledge on the matter of Picasso, having authored several biographic volumes on Picasso (as displayed for sale at the exhibit) and as longstanding personal friend of Picassso.

Picasso’s Bull Series

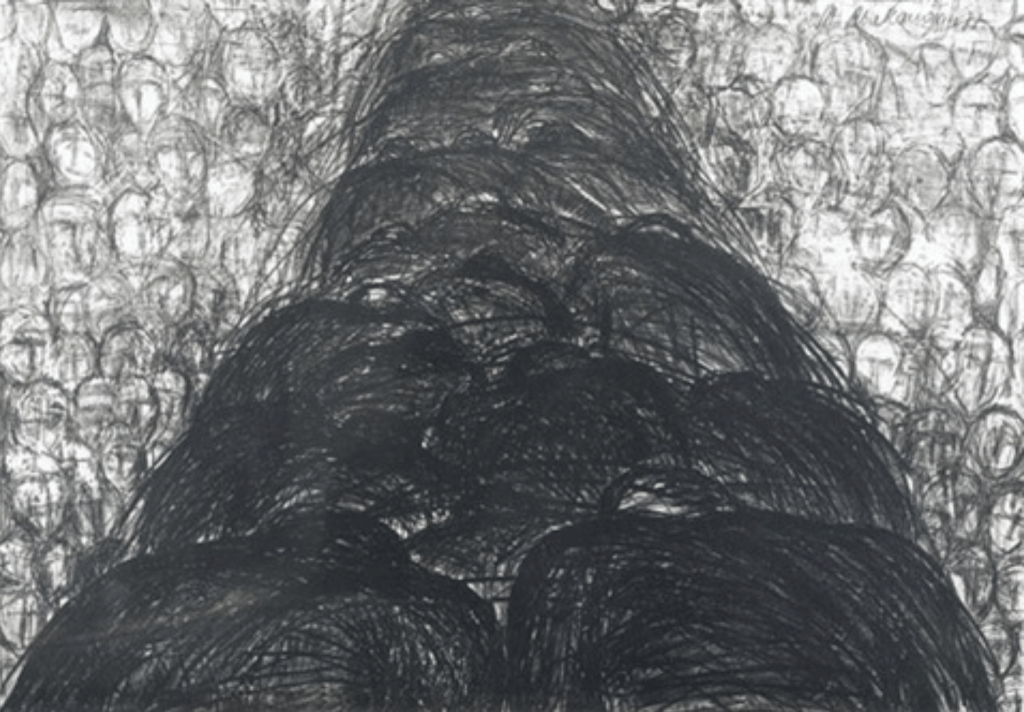

Despite having seen many of Picasso’s works exhibited before (an entirely different and much more impressive experience than seeing them in books or online) this once again allowed me a grand experience. Here I saw Picasso’s series of bull drawings, a sequence as if made specifically for use in teaching the process of reduction in art and design.

While an excellent instrument for teaching, there’s perhaps more to be understood from this series of drawings than a few concepts of design and reduction. Picasso often made it clear that he identified with the bull, making his bull drawings particularly interesting when the choices made in this reductive process is entirely Picasso’s.

To better understand Picasso, his choices and works, it helps to consider when he was born: In 1881 Brahms was still doing concerts, Edgar Degas organized and opened the Sixth Impressionists Exhibition in Paris–showing his sculpture “Little Dancer,” Billy the Kid escapes from a New Mexico jail, Sitting Bull surrenders, there was the now famous gunfight at the OK Corral, Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell formed The Oriental Telephone Company (landline telephone,) Barnum & Bailey Circus debuts at Madison Square Gardens—bullfighting was alive and well, even popular and not yet considered offensive.

In Picasso’s homeland Spain, the bull was a prominent part of their culture and while difficult to imagine today, bullfighting was entertainment. Bullfighting was a part of life and if Le Petit Picador (1889,) painted by Picasso when barely eight years old, can be any indication— bullfighting already made an impression on the young Picasso.

Picasso’s fascination with bullfighting continues and becomes a factor impossible to ignore, right from the blood and gore of bulls and horses of the bullfight, to when the bull meets its end—as dealt by the matador.

Returning to Picasso, metaphorically identifying with and relating to the bull or better yet–the minotaur as half man, half bull said “If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a Minotaur.” In Picasso’s world, the bull portion of the minotaur was ultimately destined to fight for its life and die fighting–while the man portion of that same minotaur still tries to make sense of it all.

Bullfight Symbolism

It could seem that every element of the bullfight held metaphors for Picasso, perhaps helping him to see his person in a more objective light—as the bull with all its gesturing, charging, huffing and puffing rarely wins but always fights a fight worthy of respect.

With all the cheering and commotion at a bullfight, Picasso would sit quietly through it all—as he identified with the bull, perhaps all too aware of its impending fate. For the bull it’s a fight for life and death, for the matador it’s for show and for the audience, entertainment, even with all its grotesque gore—and Picasso is the bull in his very own bullfight, to give the performance of his life and to personally pay the ultimate price. Even the horses often sacrificed in a bullfight takes on meaning, as Picasso himself sees them as a metaphor for the woman that became victims of his choices and life.

In his bull series, Picasso takes on his usual role as the artist to expertly select which elements of the bull to include or exclude, and where to draw the focus of the audience. As the number of drawings increase a progression begins to show, as detail gives way to form and design–all with the intentions of finding those essential elements of art in the subject. Picasso’s search for form and design, dissecting this subject (a bull, likened to himself) to find the art, is at this point not so different from a philosopher’s search for truth in the essence of a concept.

While the process involves an obvious reduction of elements, what’s barely noticeable at first is the price of this reduction—as the process nears the end. Intentionally or subconsciously, it becomes more apparent that art has a price.

As is frequently seen in design and icons, the bulls head is often used to symbolize unstoppable strength, mind, mentality and tenacity—clearly identifying the idea of a bull.

Picasso’s Personal Reflection

For Picasso, the symbolism of a bull’s mask was enough to suggest himself a bull when wearing it. While the later reduction in size of the bull’s head could be seen as a coincidence if a singular rendition, this was rather a gradual, consistent and therefore deliberate change. For Picasso, having associated himself with the bull and particularly the bull’s head, it would seem a fair guess that he saw his mindset to be like of a bull’s. The later reductions of the bull’s head in Picasso’s renderings would likely suggest that he experienced a gradual reduction of capacity and motivation, perhaps as brought on by age but here to the point of nearly being completely gone.

As can be concluded when viewing the Charging Bull of Wall Street sculpture other parts of the bull also has great significance. The genitals of bulls are often used to refer to the character and traits inherent to the masculinity and strength in a bull, just like people in some parts of the world compare themselves or parts of themselves to that of a bull.

Surprisingly, in a final stage of reduction—as if to make the biggest statement yet in the last drawing, Picasso almost completely castrates the bull by now drawing the genitals so small as if no longer of any significance or use.

The drawings are indisputably Picasso’s recorded expression as he chose every step of the way, which brings me to question if this was a statement on more than elements of design and abstraction, intentionally or unintentionally? Was this a commentary on art in general, the art world, or was it personal reflection, a visual autobiography (Picasso was never a man of many words?) Did Picasso perhaps feel burdened and/or drained from his own success, as he inescapably became a greater celebrity, seeing his identity, real strength and artistic freedom reduced to the point of being almost removed?